My first book, Biologists Unite, explores political realignments in global biodiversity conservation through the story of ecosystem services: an emergent field of science dedicated to analyzing, and where possible measuring, the many valuable “services” nature provides to humanity. What is at stake in ongoing attempts to recast “nature” as “natural capital”? Why did this way of thinking gain such widespread currency among conservationists? And what can the contemporary embrace of nature-based solutions like ecosystem services tell us about the changing politics of environmentalism more broadly?

The book offers an intimate, inside perspective on these hotly debated questions: an ethnographic portrait of ecosystem services shown through the predicaments of its core champions — chief among them, life scientists, endeavoring to “mainstream” the idea across a range of governance contexts — as they were forced to learn on the job (and very much the hard way) how to reckon with the political character and radical implications of our dire planetary conjuncture.

Drawing on years of participant observation conducted around two influential initiatives, the Natural Capital Project and the Intergovernmental Science-Policy Platform on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services (IPBES), the book narrates the meteoric rise of ecosystem services — an approach once heralded as the way forward for conservation — but also how fragile this strategy turned out to be when put to the test.

CHAPTER OVERVIEW

Following a big-picture introductory chapter laying out the main arguments, the book proceeds as follows…

Chapter 1 opens the story with a short vignette (“Null Finding“) that provides a brief thematic prelude to the rest of the book. Specifically, I reflect on my earlier attempts to investigate the politics of ecosystem services in my home province of British Columbia, Canada (BC), where I failed to make that case work as a third empirical anchor to my dissertation (alongside the Natural Capital Project and IPBES). While my doctoral research was supposed to be studying the “rise” of ecosystem services, I saw the notion “fall” precipitously out of the picture as a salient part of environmental politics in the province. Eventually, I had to let go of the erstwhile case study. In retrospect, I propose that the conspicuous collapse of ecosystem services in BC remains broadly instructive. Indeed, the abandonment of ecosystem services by the main environmental groups in the province may offer encouraging clues about the prospect of releasing the countless other “unfree radicals” I met throughout my travels who described feeling trapped by such notions.

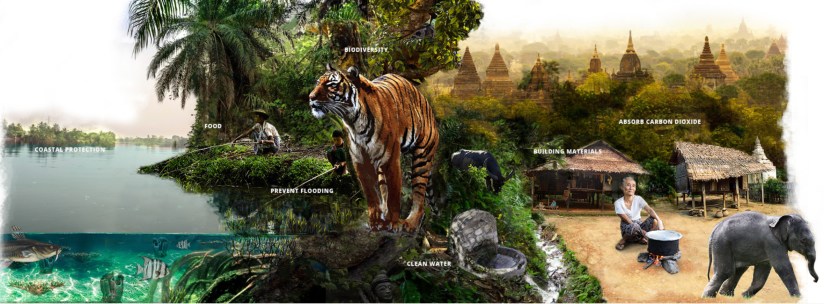

In Chapter 2 (“Transmutations at the Frontier of Natural Capital“), I begin a three-part deep dive into the Natural Capital Project: a storied group that has remained at the vanguard of the ecosystem services movement since its inception. Here, I outline their theory of change, their general mode of operating, and their prolific worldwide interventions. I spend much of the chapter showing how practitioners actually mobilized ecosystem services out in the field by portraying one of the group’s many mainstreaming operations in action. Specifically, I describe traveling to Myanmar, where I investigated several “breakthroughs” WWF and the Natural Capital Project had achieved while trying to intervene in what they perceived to be a critical window of opportunity in the country. I unpack the reasoning that led WWF to embrace ecosystem services and examine how they attempted to operationalize this strategy. Throughout these examples, I highlight the considerable skill and painstaking effort needed to wield ecosystem services and make it function as intended (insofar as it did at all). I observed ecosystem services assuming many different shapes and configurations, evincing a malleable set of practices subject to creative improvisation. In contrast to accounts of ecosystem services emphasizing its putatively abstract and impersonal calculations, I show how its situated enactments were in fact deeply embedded, rather lively, crowded, and very much full of people.

In Chapter 3 (“Realigning Conservation“), I delve yet deeper into the constitutive operational functioning of ecosystem services to show how widespread efforts to “mainstream” the concept have required not only hard work but very distinctive forms of work. To this end, I introduce a general framework for describing the key types of conditions (fragmented fields), practices (bricolage), actors (institutional entrepreneurs), and power relations (hegemonic), which have together underpinned ongoing efforts to realign the forms and functions of conservation through ecosystem services. While these dynamics have all been directed toward influencing the behavior of those ultimately responsible for producing environmental impacts (i.e. powerful decision-makers), I show how a key effect of these widespread deployments of ecosystem services, taken in aggregate and repeated in intervention after intervention, has been to change the internal logics and institutional composition of conservation itself. Although the Natural Capital Project’s stated mission has been articulated around a vision of “aligning economic forces with conservation,” when considering the profound power asymmetries shaping these dynamics, I suggest this process may have instead worked in reverse: as a realignment of conservation around a hegemonic conception of “economic forces.”

In Chapter 4 (“Course Corrections“), I examine the obstinate political realities that confronted the Natural Capital Project’s multi-decade campaign to mainstream ecosystem services and how its personnel made sense of these confrontations. Over the years, they had to draw (and redraw) many lessons while grappling with an array of challenging field projects that regularly surprised and frustrated their efforts. By tracing these “course corrections” and the social dynamics by which they came about, I analyze how the Natural Capital Project started to recognize their baggage — the variety of unexamined assumptions lodged in their inherited theory of change — some of which they were forced to abandon. Central to this learning process, I contend, was the need to develop (rather than carefully bracket out) a more critical engagement with questions of power, political economy, and social change. Yet at the same time that the Natural Capital Project gazed repeatedly into such realizations, they backed away from allowing themselves to fully accept the implications. While the outcome of this process remained ambiguous, these various adaptations and ambivalences nevertheless offered modest evidence of political “wiggle room” in ecosystem services.

In Chapter 5 (“Unmainstreaming Natural Capital“), I begin a two-part analysis of IPBES. In this chapter, I describe how epistemic and political struggles over ecosystem services started to erupt inside the Platform. The IPBES process offered a clear reflection of growing tensions within the field of ecosystem services, but it also ended up functioning as an important discursive arena in its own right, where these tensions were being actively deliberated on, vigorously contested, and settled through numerous rounds of negotiation among its membership. In that context, I introduce an eclectic cast of “epistemic dissenters,” operating from inside the Platform, who were attempting to bring a range of heterodox, subaltern, and critical perspectives into the process and who were trying to redirect IPBES itself toward the production of knowledges less bound to neoliberal logics and potentially more amenable to transformative and even radical alternatives. In analyzing these attempts to reclaim (or at least destabilize) the meaning of ecosystem services, the chapter begins to assess Noel Castree’s suppositions regarding “unfree radicals” through a unique context where critical scholars tried to accomplish something resembling these speculations about a “more deeply radicalized” global change science.

In Chapter 6 (“Battleground Ecosystem Services“), I trace how these epistemic transgressions within IPBES unfolded and with what sorts of effects: how dissenting experts maneuvered the process to renegotiate mainstream positions, profane established orthodoxies, and create openings for more critical understandings of the historic crises which IPBES was created to address. Focusing on the first IPBES work programme (2014-2018), I analyze two contested processes that were key to shaping the early institutionalization of the Platform — the development of its official Conceptual Framework and the formation of its expert group on valuation — both of which became critical hotbeds of epistemic dissensus. Crucially, these subversions relied on a wider, reciprocating array of other experts distributed throughout the process to also play their part. While most participants had come to IPBES with fairly mainstream views about what ecosystem services meant, I saw many of these scientists, after being introduced to alternative and heterodox perspectives, and after years of engagements with critical scholars, growing to like these more transgressive and radical approaches. Reflecting on these clashes, I propose that the contested knowledges and ambivalent scientific subjects caught up in ecosystem services were neither lost causes nor beyond redemption.

Finally, in the Conclusion (“The Friends We Made Along the Way“), I step back to consider the narrative arc of the book as a whole and its account of the rise and fall of ecosystem services and the biologists who once united around it. Although the fervor surrounding ecosystem services has receded from its earlier extremes, I conclude that the deeper dynamic it instantiated contains important lessons that have remained salient. When considering the turbulent transformations that occurred while undertaking this research (and since), the politics of ecosystem services can offer instructive examples — cautionary warnings, to be sure, but also some generative provocations and even a degree of inspiration — with continuing relevance to the dilemmas facing contemporary movements today: those now struggling to find their footing as they position themselves in relation to, and sometimes against, the forces eradicating biodiverse life on this planet.