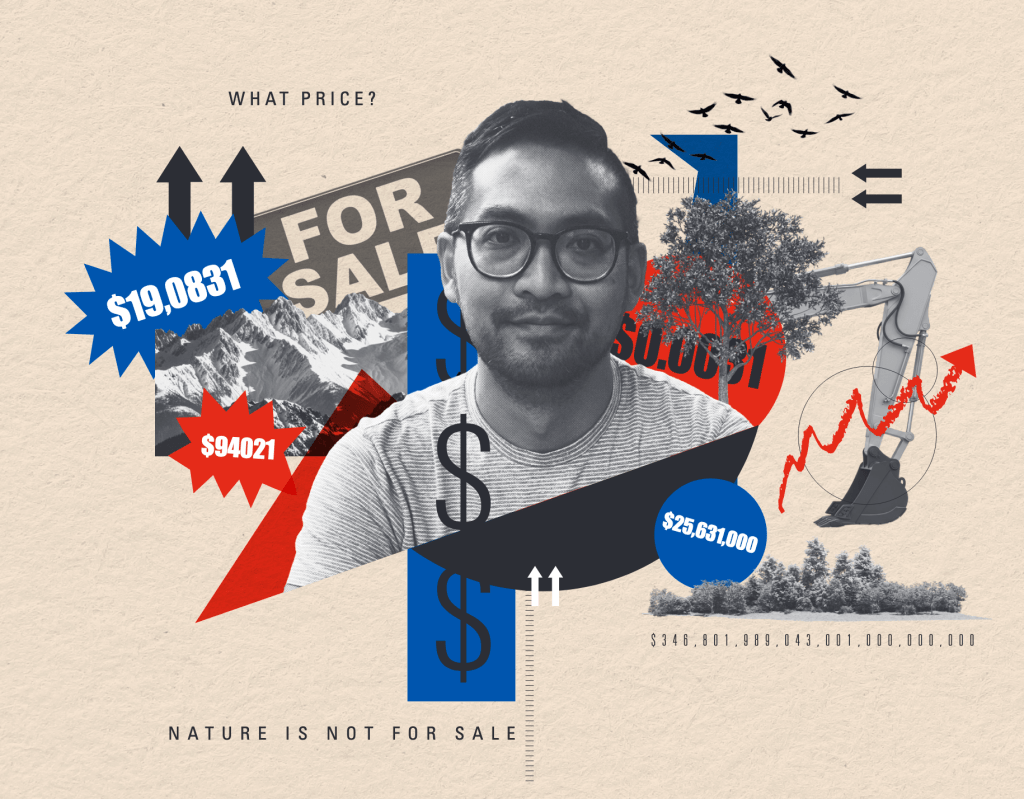

New Scientist just published a neat feature story about my book, which includes our interview and this evocative image of me emerging from an explosion of dollar signs and random numbers.

New Scientist just published a neat feature story about my book, which includes our interview and this evocative image of me emerging from an explosion of dollar signs and random numbers.

I’m excited to share that my first book, Biologists Unite: The Rise and Fall of Ecosystem Services, is officially published and now available at MIT Press.

I organized my first symposium!

Radical Implications — The climate crisis confronts each of us with urgent questions and bewildering choices about what to do, what to learn, where to go, and who to be at this momentous historical crossroads. In this Clifford Symposium, we will bring together students, faculty, staff, and the wider networks of which Middlebury is a part to discuss our roles as we face increasingly turbulent futures. What can, and should, college be offering to young people as they prepare to join this pivotal moment? How are we all reimagining our disciplines, our communities, our futures? What does it mean for our students — from dancers and economists to marine biologists, elementary school teachers, and computer scientists — to be coming of age in an age of planetary crisis and transformation? And what would an education that is proportionate to the radical implications of the climate crisis look like?

Here’s a quick sketch of the programme (and here‘s the full thing):

Hostile Terrain 94

Jason de Leon’s haunting exhibit, Hostile Terrain 94, will be installed in McCullough, with opportunities for people to offer reactions and reflections (via sticky notes, writing, drawings, etc.)

Panel Discussion — 350.org Reunion

Bill McKibben joins the other co-founders of 350.org (all Middlebury alums) to reflect on the past decade of climate activism, on successes and failures, and on what’s changed (and what hasn’t, and what must) in the climate movement.

Keynote — Sarah Jaquette Ray

Sarah Jaquette Ray, author of A Field Guide to Climate Anxiety and co-creator of the Existential Toolkit for Climate Justice Educators, will address the powerful emotions inherent to facing the climate crisis and how to navigate them.

Panel Discussion — Faculty Perspectives

Carolyn Finney joins an interdisciplinary group of Middlebury faculty to discuss how they are grappling (not always successfully) with the radical implications of what is now unfolding.

Keynote — adrienne marie brown

adrienne maree brown, author of Emergent Strategy and Pleasure Activism, and co-host of How to Survive the End of the World, will conclude the first day of the symposium by addressing themes of activism, movement strategy, and social change and transformation.

Keynote — Jane McAlevey

Jane McAlevey, legendary labor organizer and author of Raising Expectations, No Shortcuts, and A Collective Bargain, will share her analysis on what the fight for climate justice can learn from the legacies and continuing struggles of the labor movement.

Keynote — Mary Annaïse Heglar

Mary Annaïse Heglar, climate justice activist, writer, and host of the Hot Take podcast and newsletter, will address the experience of coming online as a young person into such an outrageous situation.

Panel Discussion — Arts & Humanities

A group of Middlebury arts and humanities faculty join together to discuss their perspectives on and approaches to making sense of, relating with, and intervening in the many compounding urgencies intersecting around the climate crisis.

Student Perspectives

In this student-organized event, students themselves will share their own reactions to and reflections on the big questions that define the themes for this symposium; student organizers will help connect these big questions to traditions of activism on this campus and ways of getting involved.

Keynote — Julian Brave Noisecat

Julian Brave NoiseCat, member of the Canim Lake Band Tsq’escen and a descendant of the Lil’Wat Nation of Mount Currie, is a writer, journalist, and activist. His keynote will conclude the second day of the symposium by helping us connect the dots brought together in the climate crisis (and by this symposium), taking stock of how we got here, where we are, and where we must go (and who is this “we,” anyway?).

Social Gathering

This social event will make space for attendees to blow off steam after engaging with the symposium’s big topics.

Living Life at the Knoll

The Knoll will provide an intentional space for socializing, enjoying the day, and getting on with the task of living lives amid planetary turbulence and transformation.

Last week I got to do a big public interview with Naomi Klein, whom we’d invited to Middlebury to give the 2020 Margolin Lecture.

We began by watching A Message from the Future, her short film envisioning what a successful Green New Deal could look like, followed by an introduction by her friend, Bill McKibben. Naomi then delivered a powerful lecture tracing the interlocking crises — social, political, economic, ecological — that define the current moment, and the proportionately integrated forms of struggle needed to confront these crises. We left plenty of time for discussion. I posed a series of questions synthesized from conversations with students exploring what it means to be coming of age in an age of climate breakdown before opening it up to questions from the audience. The place was packed and pretty lively, with folks squeezed into the aisles, spilling out into the hallways, and ultimately rising for a big standing ovation at the end.

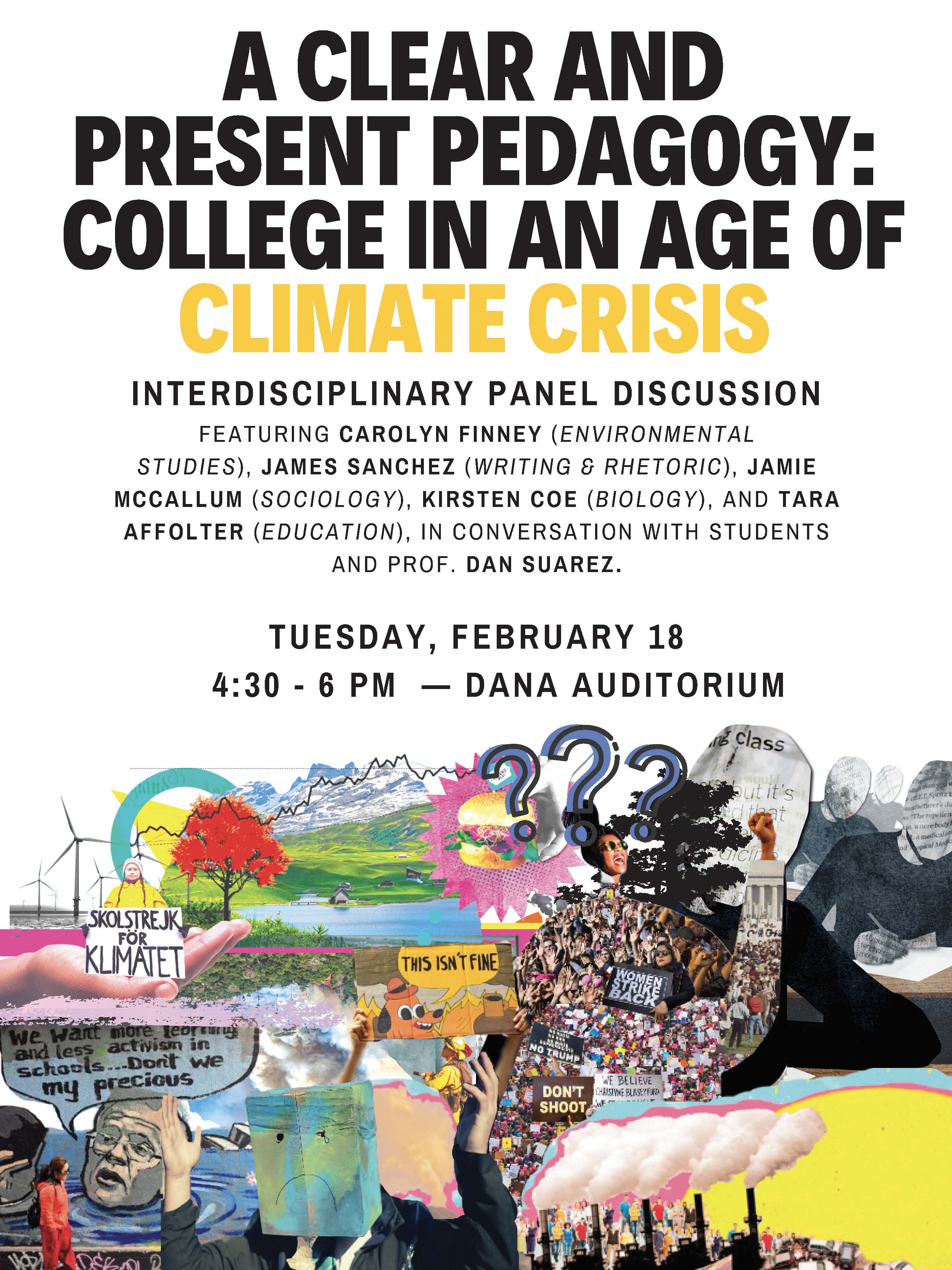

To continue building on the themes of Klein’s lecture, I also organized a follow-up panel the next week broadly themed around my ongoing project, A Clear and Present Pedagogy. I invited an interdisciplinary group of colleagues including Carolyn Finney (Environmental Studies), James Chase Sanchez (Writing & Rhetoric), Jamie McCallum (Sociology), Kirsten Coe (Biology), and Tara Affolter (Education), to engage in dialogue around the following prompt:

The climate crisis confronts each of us, including and especially young people, with urgent questions and bewildering choices about how to live, who to be, what to learn, where to go and what to do at this momentous historical crossroads.

Building on Naomi Klein’s Margolin Lecture from the previous week, this event will bring together students and faculty to discuss how and why college (i.e. what we’re all doing right now) might matter, or might come to matter, as we confront increasingly turbulent planetary futures. What can (and arguably should) college offer to young people as they prepare to join this pivotal historical moment? What does it mean for our students — from dancers and economists to marine biologists, elementary school teachers, and computer scientists — to be coming of age in an age of climate catastrophe? And what would an education that is proportionate to the dire urgencies and radical implications of the climate crisis look like?

I was excited to learn that the student organizing collective I’d been working with on this event had nominated two freshman students to represent them, one of whom produced this sick poster, and both of whom crushed it at the event with their thoughtful and earnest (and challenging!) questions.

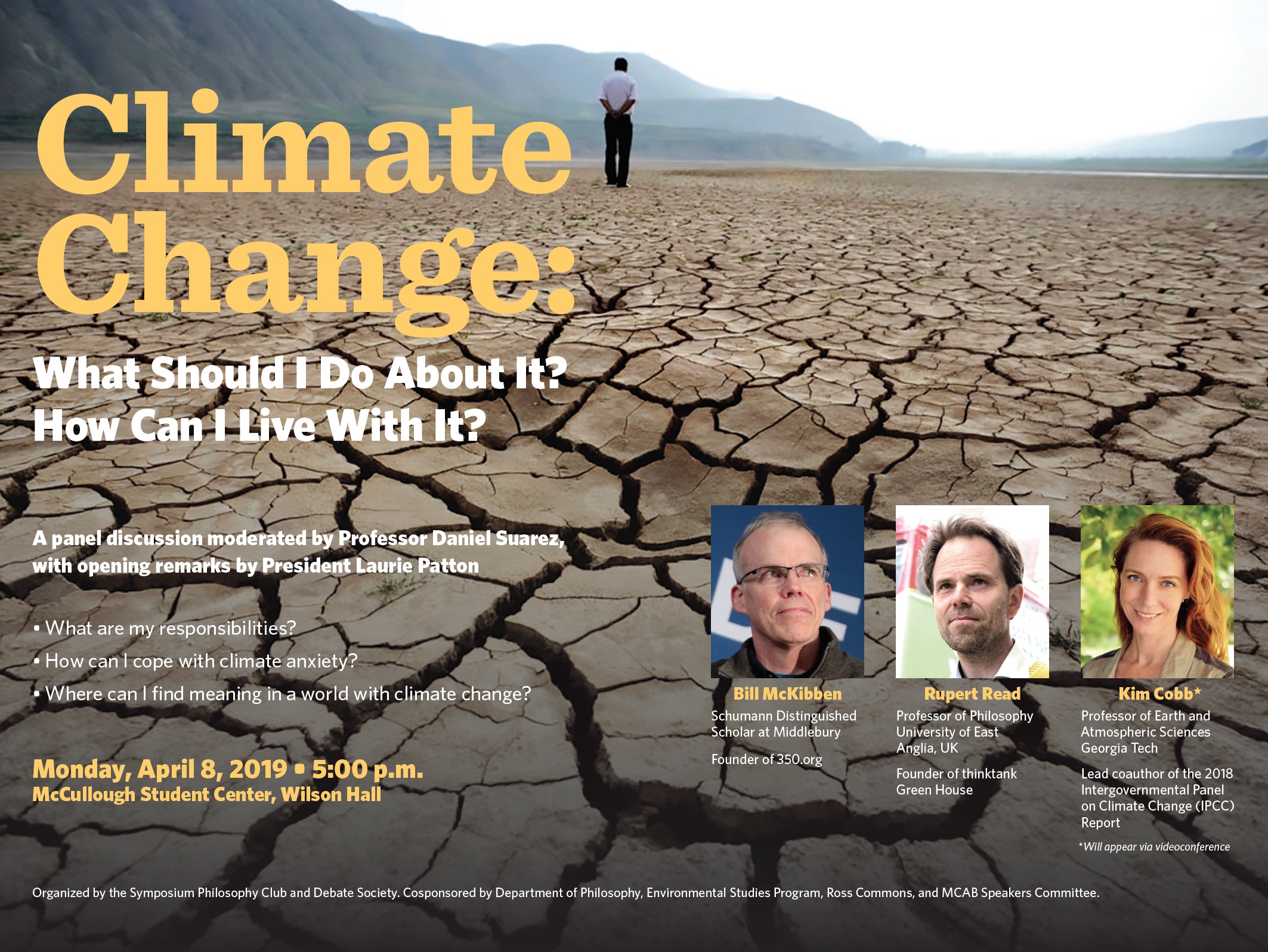

I moderated a student-organized panel discussion several weeks ago about making the best, or maybe just making sense, of a bad situation.

I was joined by Bill McKibben (co-founder of 350.org and Middlebury’s very own environmental scholar-activist in residence), Rupert Read (an environmental philosopher and key proponent of Extinction Rebellion), and Kim Cobb (an oceanographer and lead author of that grim climate report)

I recently appeared on Vermont Public Radio’s Brave Little State. I helped introduce the idea of environmental justice and highlighted the blind spots that come with universalizing narratives like that of the so-called “Anthropocene.”

I recently appeared on Vermont Public Radio’s Brave Little State. I helped introduce the idea of environmental justice and highlighted the blind spots that come with universalizing narratives like that of the so-called “Anthropocene.”

Click here to listen.

The whole episode is pretty engaging and focused on the question, “How Is Climate Change Affecting Vermont, Right Now?” During our interview, I discovered that the host, Angela Evancie, is a Midd alum who remembers being around during the formation of 350.org back in the day. She explained how each episode of her show is structured around a question posed by a member of the community. It was great to see how artfully her team structured the story and just to listen all of the other interviews with various experts, and assorted Vermonters, narrating their experiences with the escalating disruptions of global warming.

I submitted my dissertation last Friday to UC Berkeley — December 15, 2017. In practical terms, that means I have concluded my doctoral program and am one piece of paper — and a lollipop as per university policy — away from receiving my PhD. Below is the abstract for “Mainstreaming Natural Capital: The Rise of Ecosystem Services in Biodiversity Conservation.”

This dissertation investigates the growing influence of “ecosystem services” (ES) ideas in biodiversity conservation. Once an esoteric neologism, ES refers to the conceptual framework and now-burgeoning field of research and practice dedicated to analyzing in measurable, often monetary terms the various “services” provided by nature to people. Over the past two decades, diverse communities of practitioners around the world have increasingly come to accept, and even to embrace, the emergent policy discourse formed around ES. In this dissertation, I explain how the concept of ES has come to gain such widespread currency among conservationists, what is at stake in re-envisioning biodiversity in this manner, and what the contemporary embrace of ES can tell us about the changing politics of conservation.

I explore these questions through sustained, close-quarters engagements with some of the idea’s core champions. I provide a thickly-described account of the politics of ES through the experiences and perspectives of those working at the forefront of efforts to “mainstream” its tenets across diverse contexts of environmental governance. My analysis draws on encounters with ES practitioners operating through two prominent initiatives: (a) the Natural Capital Project and (b) the Intergovernmental Platform on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services (IPBES). Through organizational-ethnographic research embedded with ES experts, I examine concerted efforts to institutionalize ES in conservation (and beyond) as the prevailing framework for making sense of, advocating for, and ostensibly saving nature.

I describe a campaign seeking to re-assert conservation’s viability by aligning it to ‘fit’ more neatly within dominant discursive, institutional, and political-economic orders. In this context, ES provides an important operational means of enacting these re-alignments. I portray the organizational dynamics, representational practices, and expert subjects constitutive of these efforts and draw on these findings to develop three main lines of argument: (1) the micro-social practices associated with ES are deeply implicated in the enactment of pronounced institutional shifts in contemporary conservation; (2) one of the most major consequences arising from ES relates to how it shapes the political subjectivities of those who practice it in part by internalizing a depoliticized theory of change; and (3) ES remains a contingent site of struggle, amenable to re-negotiation, with the potential to impede, but also to contribute, to more transformative, liberatory purposes other than those now enrolling it.

The dissertation will likely get posted online within a couple of months by UC Berkeley. I would be happy to share copies prior to its formal release for those interested. Thank you to everyone who played a part in this six-year journey: colleagues, friends, family, and, of course, the many people who chose to participate in this project as interviewees, key informants, and “research subjects.” It really does take a village.

The debate over putting a price on nature has spilled into another year. George Monbiot (who recently went for the jugular on natural capital) and Tony Juniper (former ED of Friends of the Earth and author of What Has Nature Ever Done for Us?) are two prominently opposed voices in this ideological fight in conservation. The debate was hosted by New Networks for Nature in last November in the UK. They go straight to town on each other’s arguments. The exchange looks to have successfully ruffled feathers among attendees, as the debate quickly spirals out from the neologism of “natural capital” per se to what it represents, what is at stake in it, and what to make of the ethical dilemmas, strategic outlook, and political possibilities it expresses.

The debate over putting a price on nature has spilled into another year. George Monbiot (who recently went for the jugular on natural capital) and Tony Juniper (former ED of Friends of the Earth and author of What Has Nature Ever Done for Us?) are two prominently opposed voices in this ideological fight in conservation. The debate was hosted by New Networks for Nature in last November in the UK. They go straight to town on each other’s arguments. The exchange looks to have successfully ruffled feathers among attendees, as the debate quickly spirals out from the neologism of “natural capital” per se to what it represents, what is at stake in it, and what to make of the ethical dilemmas, strategic outlook, and political possibilities it expresses.

The debate is watchable here (Part 1 / Part 2 / Part 3), courtesy of Cambridge TV.

Over the course of my graduate studies, I’ve grown to appreciate the power of storytelling practices in environmental politics. I have also enjoyed engaging my students around these questions. There’s this story, for instance, narrated by UNEP Goodwill Ambassador (and guy from Fight Club) Edward Norton:

And this one, produced for The Natural Capital Project:

The workings of the narratives seem easy for my students to identify: highlighting what context is established, what kind of problem is framed, and what solution is posited. Once encouraged to spot these features of the environmental texts swirling around us, it’s kind of hard to unsee. These particular clips serve as windows into the so-called “economic turn” in conservation, which my dissertation seeks to analyze, and they provide revealing glimpses into the kinds of work policy discourses can do.

I sometimes wonder how much my research questions remain salient to practitioners. Then I get to watch dialogues like this, which remind me that controversies surrounding the “business case for nature” continue to figure centrally in broader debates about conservation’s future.

The exchange is remarkable not so much because of the novelty of the arguments, which are well-worn, but in their sheer spectrum performed together alongside and in friction with one another. The debate, and the positioning of its speakers, feels reflective of the tenor of ecosystem services discourse more generally. Peter Kareiva (The Nature Conservancy) and Jeremy Oppenheim (McKinsey & Company) begin by delivering the familiar argument: conservation must modernize by re-tooling and re-aligning itself at a broad level around increasingly dominant business actors, buiness practices, and business priorities. “That adversarial position,” Kareiva laments, “If business is an adversary of nature, nature doesn’t stand a chance.” Given the opening framing by the moderator, suggesting a false dichotomy between “capitalism” and “nature,” I was surprised by the relatively uncompromising critical stance of Lucy Siegle and especially Nick Dearden, who argued “Putting a price on nature is exactly the wrong way to go. It is further commodifying, further marketizing those things that we should actually be un-commodifying and un-monetizing.” Dearden later returned to this point on economic valuation, concluding emphatically, “I am firmly against this. […] I think we’ve really got to kill this idea that this is the way to save the environment.”

The debate features some customary talking past each other with different speakers using different understandings of the words they are using. But they also tackle head on some of the underlying contradictions that ecosystem services arguments pivot around. The debate wanders through a variety of core issues in ecosystem services debates, from the the prospect of mobilizing private investment for conservation, to the ostensible failure of the 20th-century conservation movement and consequent “need” for a new way forward, and whether concepts and normative precepts in business and economics can provide it. The speakers manage to squeeze in more than a few zingers (Kareiva quips, “Money can’t buy you love? Money can buy you nature!”)

I was especially interested in Tony Juniper’s performance (formerly Executive Director of Friends of the Earth), which worked throughout the debate in a thoughtful and conciliatory role, smoothing over tensions, struggling to reconcile the diverse logics implicit in the arguments swirling around him. I interpret this kind of discursive work as critical to understanding the ways in which the ecosystem services framework has been unfolding among different communities of conservation practice. In contrast to the event’s title, “Money Can Grow on Trees,” Juniper’s use of economic concepts draws on ecosystem services’ other register–the economic Rosetta Stone–which allows translation between the diverse and sometimes antagonistic constituencies engaged in conservation (which was recently adopted as a kind of banner metaphor for the Intergovernmental Platform on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services).